- Home

- Chris Kenry

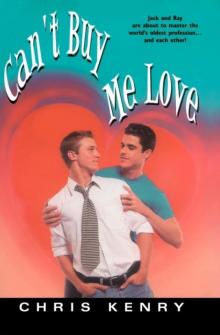

Can't Buy Me Love

Can't Buy Me Love Read online

Praise for Chris Kenry and CAN’T BUY ME LOVE

The New York Blade bestseller!

The Washington Blade bestseller!

The Philadelphia Gay News bestseller!

A Selection of the Insight Out Book Club

“With his clever observations and rapid-fire dialogue, Kenry is a

smart and funny writer.”

—The Advocate

“Well written with bold humor and witty asides.”

—Library Journal

“A romp through every gay subculture imaginable. The lead character charges by the hour, but the book will give you a charge every

minute.”

—Michael Musto, The Village Voice

“Kenry manages to charm and hold readers with his witty, fluid prose . . . a lighthearted, wonderfully silly, laugh-out-loud farce . . . This is one author whose potential will make his next book worth looking out for.”

—The Lambda Book Report

Don’t miss Chris Kenry’s UNCLE MAX coming soon!

Can’t Buy Me Love

CHRIS KENRY

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Praise for Chris Kenry and CAN’T BUY ME LOVE

Title Page

Dedication

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Epigraph

Part One - The End of La vie En Rose

1 - TRAIN WRECK

2 - ITALIAN NOSTALGIA

3 - BURL

4 - FAMILY VALUES

5 - WORK ETHICS

6 - S.I.L.V.E.R.

7 - STUFFED ANIMALS

8 - JACK HITS THE ROAD

9 - GAME PLAN REVISIONS

10 - DESPERATE MEASURES

11 - SOCIAL SERVICES

12 - TURNING TIDE

13 - MICROBUSINESS

14 - SATAN CALMS

15 - SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL

16 - LIES AND SECRETS

17 - MY OWN PRIVATE MADISON AVENUE

18 - FRO THE PAGES OF THE LITTLE SILVER BOOK

19 - LABOR RELATIONS

20 - CRAZY AL AND THE THAI STICK

21 - EXPANSION AND DIVERSIFICATION

22 - GAY MARVIN

23 - TOIL AND TROUBLE

24 - POETIC JUSTICE

25 - Parental Consent

26 - The “What” That Happened Next

27 - Scandal Is Legally Very Entertaining, Really

Part Two - La Vie En Rose

Teaser chapter

Copyright Page

For my two wives, Jim and Jeff

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Pete Lindstrom, Jim Holik, and the Duchess, for helpful readings; to Quin Wright and Tracy Weil, for technical assistance; to Kevin Dougherty, for having such a perverse library; to my family and to Bill Weller, for being there; to David Maddy (and the group of bored US West trainees), for the penis paintings, and for more filthy epigrams than I could ever have possibly imagined.

Thanks especially to Alison Picard and to John Scognamiglio, with whom it has been a pleasure to work these past few months.

“Immaturity” is one more word that requires definition. To men it means the inability to stand on one‘s own two feet. A woman flings it at anyone who doesn’t want to marry her. Here I find myself for once inclined toward the masculine view. I feel that, though no one must ever deny his dependence on others, development of character consists solely in moving toward self-sufficiency.

—Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant

Part One

The End of

La vie En Rose

1

TRAIN WRECK

Even now, almost five years later, I still wonder what Paul was thinking. I guess only God knows, and He is being decidedly silent on the subject. Paul was my lover. I say was because he no longer is. He stepped off the curb one bright April afternoon and was struck, dragged sixty-eight feet, and killed by the light-rail train, and thus, to establish a metaphor, derailed my life from the effortless track on which I had been traveling.

The controversial light-rail system had been in place for nearly a year when it happened, and people were only just beginning to get used to it. In its first few months of operation, several cars and a few pedestrians had been struck, so the city’s transportation authority mounted a vigorous ad campaign warning people to pay attention to the trains and not, as many people did, try to race them. It was an annoyingly thorough campaign, with billboards and bench ads everywhere, and one that Paul was surely aware of, so ignorance can’t have been the reason. Nor can it be entirely explained by the fact that he was an Englishman, and as such was used to looking to the right instead of to the left, and had possibly looked the wrong way before he started crossing. The transportation people, for obvious litigious reasons, liked this theory, as did the newspapers, since it gave the story an interesting twist, but Paul had been living here for over twelve years by then, in which time he had crossed many a street safely, so that probably wasn’t very likely either.

I myself theorized that it happened because he was an architect. In fact, that was what had first attracted us to each other. He was an architect and I was an art history major. We shared a love of architecture and were both distressed by the impending destruction of a building designed by I. M. Pei, a swooping parabaloid structure that had been part of a failed department store and was soon to be torn down. This incensed Paul, who loved both Pei’s work and the city of Denver (in which he, Paul, had made his fortune), so he quickly organized a grassroots committee to have the parabaloid designated a historic landmark, and thus thwart the destructive plans of the developer. But, alas, in vain, as the politicians in our fair state of Colorado, most of whom still think the sun circles the earth, could not see something built in the late 1950s as having any historical significance whatsoever. Now, if it had been a sports stadium he was trying to preserve . . . But I digress. The reason I think the I. M. Pei parabaloid was responsible for his errant step into mortality is this: presumably he was walking back to his office from lunch that afternoon and had just strolled past the building a few blocks before he reached the tracks. Having seen it, he was probably preoccupied with its imminent destruction, and was surely thinking of ways to prevent it when he should have been looking where he was going.

It was a neat and tidy explanation, and one I eagerly fed to friends and family for months afterward. It seemed plausible and palatable enough, but unfortunately that doesn’t make it true. I could point to several different possibilities for Paul’s lapse of attention, but as wise Gandhi once told his whining grandson, “Every time you point the finger of blame somewhere else there are three fingers pointing back at you.”

So with that in mind I have to admit that I suspected that Paul’s mind was preoccupied with nothing other than yours truly. The three fingers were undeniably pointing to me as the probable cause of his demise, and I knew it.

If my suspicions were in fact correct, and I was clouding his thoughts, I hoped at least that he was thinking of me fondly and remembering all the happy times we spent together—the many trips we’d taken, the sex-filled afternoons, the look and feel of my chiseled body, the beautiful garden I’d painstakingly landscaped, the Christmas dinners and the birthday parties I’d planned and executed. In short, how deliriously happy I made him.

But who was I kidding. Earlier, on the very same day he was killed, we had what my parents like to euphemistically call “a discussion.” And, in truth, it was a very parental discussion: he was the parent; I was the child. In it he told me, in no uncertain terms, that although he loved me and had never minded supporting me “in quite high style” wh

ile I decided what I was going to do with my life, I was now twenty-five, had been out of college and jobless for nearly three years, and really needed to do something other than work out, tan, read magazines, and plan entertaining and expensive dinner parties. And of course he was right. Looking back, I see that my lifestyle then was hedonistic in the worst sense, but I honestly didn’t see it that way, and thought he was being unnecessarily petty. Didn’t he see that I worked very hard? That in my own way I was highly disciplined? I worked out five times a week, sometimes twice a day, I spent months landscaping the side yard and redecorating the house, and when I wasn’t doing that I was busy improving my mind and making myself a more informed member of society by reading Time and Architectural Digest and The Economist (in addition to People, Us, Vanity Fair, Details, Men’s Health, W, Spin, and The National Enquirer).

And yet somewhere in the deepest darkest recesses of my mind I knew he was right. I had gotten lazy, and all of the “work” I was doing was just an excuse, although an excuse for what I had no idea at the time.

Because he loved me, Paul had allowed me to lead a very cushy existence, and I suppose it was inevitable that the spoiled child had begun to take for granted the one doing the spoiling. All the more so because I knew that despite our argument he would never take action on his frustration. He would never make me get a job, would never cut off my pipeline supply of money. Paul was whipped, and all I had to do to smother his misgivings was have raucous sex with him and afterward tell him how much I loved him, would always love him, and on and on and on.... So when he blew up at me that morning as I headed out to my lawn chair by the pool with the new issue of Entertainment Weekly and a bottle of Pellegrino, I barely lifted the earphone of my Walkman to listen, but made a mental note that I’d have to put on quite a show in the sack later that night. He yelled and pleaded with me there in the kitchen that morning, and I’m sure that my eyes, safely hidden behind my sunglasses, were rolling in their sockets at the silliness, the pettiness of it all.

By now you are probably wondering who I am. Call me manipulative, or selfish, or lazy, or even Ishmael, if you like, but my real name is Jack. Jack Thompson. My mother is a devout Democrat and a big fan of the Kennedys, so I was named after President Kennedy, which is fine by me, because I was actually born under Nixon’s reign, and I’d hate to be called Richard, although Dick might have been a more appropriate name, considering. My upbringing was what you could call upper middle class, and I have spent my whole life right here in Denver, Colorado. Oh, I went away to college and have traveled, but for some reason I’ve always returned. I used to wonder why I came back. Denver is not an especially cosmopolitan city, and I’ve often thought myself more suited to New York or Boston or San Francisco, but for me Denver always seemed safe, and I suppose that is why I never left for long. I don’t mean safe in terms of the crime rate or the climate. There are plenty of drive-by shootings and paralyzing blizzards to make one feel insecure, but Denver felt safe because I knew it was a place where I would always be taken care of. Trouble might arise but someone, usually my parents or Paul, was sure to squash it back down for me.

Even right after Paul’s death, when I really should have been afraid, I still felt fairly safe. I went to the morgue to identify him, which was a grisly task as half of his face had been scraped off, and fretted only about what to do with the body. No worries about the loneliness ahead of me or the whereabouts of a last will and testament. No, just a small worry about what should be done with the corpse. My best friend Andre, who is not squeamish about death, having nursed one dying lover himself, went with me.

“Girl,” he said as we left the morgue (on Planet Andre, everyone is a “girl”), “I suggest cremation, but if that’s not an option then definitely a closed casket.”

But as it happened, even that decision was not one that I had to make. In fact, shortly after his death, every decision regarding Paul and his estate was made for me, even when I decided that I did want to have a say in the matter.

Enter Wendy.

Paul’s only living relative was an elder sister, Wendy, who was named sole executor of her brother’s estate. Wendy and Paul were not close. In fact, in the three years I’d been with Paul there had never been, to my knowledge, a phone call or letter between them. She had never approved of her brother’s “lifestyle choice,” and had, for all intents and purposes, lobotomized him from her memory. However, upon her hearing of his death and discovering that he had become a fairly wealthy architect, her memory suddenly returned, although it certainly did not soften, and, like some atomically mutated monster, she emerged from her lair, wreaked havoc, and then retreated again to where she’d come from.

She arrived at DIA less than two days after being notified of the accident, took a suite at the Brown Palace, and set to work finding a lawyer. When she hired one, she made it his first priority to have me forcibly removed from the house by some very large men with very legal eviction papers, who started changing the locks before I’d even left.

I met her only once, with her lawyer, when I was allowed back into the house late one afternoon to collect some of my belongings, but it was a meeting that had lasting effects on the rest of my life. She was what Andre would call an “old Irish potato,” meaning she was best described by adjectives like “tweedy” and “ruddy.” She smoked endlessly and had, I noticed, developed deep wrinkles around her mouth from the decades of repeatedly forming it into an O around her cigarettes. As the day went on, her crimson lipstick would work its way into these rivulets, making her mouth look all bloody, as though she’d just finished devouring her young. I remember thinking as I watched her that if Paul had aged as gracelessly as she, maybe it was better that he had died relatively young.

Knowing little about Wendy, and naively figuring I’d give her the benefit of the doubt despite the fact that she’d had me evicted, I tried to reason with her as we—she, the lawyer, and I—sat in the living room of the house Paul and I had shared, cardboard boxes littering the floor. They were seated on the bank-green Chesterfield sofa that I’d always loved, and I sat opposite them on one of the cardboard boxes, the rest of the furniture having been packed away or sold.

I have a tendency to gush when I am nervous, filling up awkward silences with a flood of words, and so it was then as she and the lawyer sat stonily observing me, saying nothing. I told her that I completely understood her having me removed from the premises when she did not know me from Adam, seeing as she and Paul had been out of touch for so long. I told her how much I’d loved Paul, and how an hour didn’t pass that I didn’t think of him. I told her all about the memorial service and the flowers I’d ordered and the poetry I’d recited. I then went on to say that I hoped she and I could share our grief, maybe console each other, give each other a shoulder to cry on, and I’m afraid I even shed a few tears.

Christ, why didn’t somebody stop me? If Andre had been there he certainly would have. He’d have yanked me out into the hallway and hissed, “Girl, why don’t you shut the fuck up! That bitch doesn’t care! She thinks you two were Sodom and Gomorrah living here. She doesn’t want to share any of your damn grief!”

And it was true; she had no interest in hearing any of the lurid details of her brother’s seedy life, let alone commiserating his loss with me. In fact, my attempts at commiseration probably had the reverse effect and turned her against me more than she already was. But in the absence of levelheaded Andre, on I gushed. Finally it was Wendy herself who intervened.

“Mr. Thompson,” she said, crushing her cigarette into a piece of venetian glass, which, in retrospect, I should probably have restrained myself from telling her was “never meant as an ashtray.”

“It’s nice to know that my brother was so, uh, loved in his lifetime . . .”

Here she paused and took one of my hands between her dry, scaly fingers, her voice annoyingly condescending. “. . . and I can tell you’re upset. It’s all been quite a shock. Nevertheless, we have to pick up the pieces an

d carry on, so I think we’d really better get down to the details, as I haven’t much time left, and Mr. Branson”—she gestured with her pointy beak of a nose to the attorney—“is on a tight schedule as well.”

I nodded, wiped my eyes with the tissue she’d pulled from her sleeve, and took a deep breath. She patted my hand, released it, and leaned back into the sofa.

“I don’t know what financial arrangement you had with my brother, for, how shall we say . . . services rendered....” She paused here, and I looked at her for a few moments honestly bewildered, like a foreigner being given complicated directions. A deer in the headlights. Blink. Blink.

“Well,” I muttered, “nothing was ever really spelled out, but we were essentially married and managed things the way most married couples do.”

She winced visibly when I said the word married, and took another cigarette from her maroon box of Dunhills, lighting it with a cheap plastic lighter she took from the pocket of her sweater. I went on. “Paul was carrying most of the financial load, until I, uh, got settled into a career.”

“Yes, I see,” she said, inhaling deeply. “And what line of work are you in now?”

I hesitated, but continued, flattered that she seemed to be taking an interest in me. “Well, I studied art history and classics in college, so ideally I’d like to do something in one of those veins. Paul really encouraged that. He was always trying to get me an internship at the Art Museum, or a job in a gallery, but, well, I guess I just never found my niche, so to speak.”

“And what do you do now?” she repeated, her voice tinged with impatience.

“Uh, now? Well, let’s see, mostly I’ve been working as a sort of weight trainer at a gym and teaching some swimming lessons. It pays a little, but I usually take it out in trade.” I smiled shyly. “For workout privileges and supplements,” I added.

Can't Buy Me Love

Can't Buy Me Love